Growing Up or Growing Old?

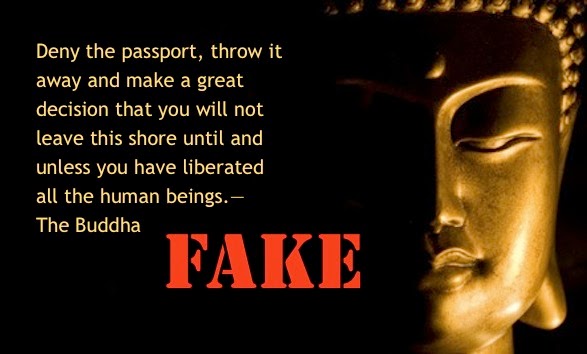

“Deny the passport, throw it away and make a great decision that you will not leave this shore until and unless you have liberated all the human beings." — The Buddha

This quote is all over the internet, usually without citation. There is a good reason why there is no citation showing the source of the quote. It is virtually impossible for the Buddha to have said this. First because it contradicts everything the Buddha said, but it also ignores the nature of mind.

The quote is said to come from the Diamond Sutra. Well, what does the Diamond Sutra really say about this?

“If a Bodhisattva announces: I will liberate all living creatures, he is not rightly called a Bodhisattva. Wherefore? Because, Subhuti, there is really no such condition as that called Bodhisattvaship, because Buddha teaches that all things are devoid of selfhood, devoid of separate individuality. Subhuti, if a Bodhisattva announces: I will set forth majestic Buddha-lands, one does not call him a Bodhisattva, because the Tathagata has declared that the setting forth of majestic Buddha-lands is not really such: ‘a majestic setting forth’ is just the name given to it.” — From The Diamond Sutra, §17, No One Attains Transcendental Wisdom

This is a far cry from the popular quote. The Diamond Sutra can say that there is no such a thing as the Bodhisattva path because the author was simply restating what the Buddha had actually said.

There are some ideas and practices in contemporary Buddhism that are better left unannounced. Other ideas could stand some explanation. Just as the Pure Land, Amitabha and so forth are best seen as symbols, the Bodhisattva path might also be better served as being presented as a symbol rather than a literal truth. The sad reality of humanity is that many would rather hold on the illusion of solidity.

Like ostriches that hide their head in the sad at the approach of a threat, we often do the same. Okay, the ostrich hiding its head in the sand is a myth. It doesn’t really do that. It runs away from danger. But the ostrich makes a great symbol, and has for hundreds of years, just as the bodhisattva has been a great symbol for a couple of thousand years or so. We need symbols to explain our actions and views, our biases and prejudices. Some people cling to some of the popular New Age philosophies or some other religion to help them “contend with difficulties” with their own insecurities.

The issue is the tendency to compartmentalize our mind(s). It is as if we have a committee inside our head. We like to call it “the mind.” The internal committee is rarely in order. The reason for this is that this “mind” is made up of the many hundreds of selves we’ve accumulated during our life while trying to negotiate ourselves into a position of happiness. Each “self has a strategy to gain happiness but the many selves often work at odds with one another.

Sometimes or standards of happiness were somewhat unsophisticated and the pleasant feelings were easy to attain. At other times we just aren’t paying a lot of attention to what makes us happy and our strategies reflected this. When I was a child I used to throw temper tantrums to get what I wanted. It usually worked because my mother so very embarrassed by her “loud barbarian,” as she called me. I wasn’t particularly interested in the particulars of the results, just the feeling of being pleased seemed important. Like the child in me, the committee members in my mind lean toward to the deluded camp. Sometimes the results that I thought were so pleasing at the time turned out to be destructive later in my life. I didn’t know that my mind was deceptive and downright dishonest.

The purpose of the Buddha's teaching is the mastering of the perceptions we have of our self and not-self. The Buddha’s intent was to bring clarity, honesty, and integrity to our being to the calm the committee, to lead them toward a more skillful strategy of happiness.

The symbol of the mental committee might be helpful, even though it makes us sounds like a species of schizophrenics. It often seems that the committee members aren’t talking to each other. Our reality becomes fragmented. We create more “me” and “you” than we can successfully deal with. When this happens the “enlightened” committee member and the “judgmental” one might not be on speaking terms. The judgmental member might be in communication with the “insecure” one, and the judgmental committee member is a liar. The many selves that make up a human being can’t act out authentically unless they are integrated into a whole.

This integration is difficult for the worldling and often we use symbols to explain what it is we are trying to do. The Buddha himself is one such symbol. No one knows what the historical Buddha was like. All we have is an abstract of a human being we find in the Nikayas. No one knows what Buddha is like. All we have is the mythology of the Sanskrit canon, another abstract. Both are simply symbols. We use the symbols that resonate with us. As we grow and evolve our symbols also grow and evolve. If we grow skillfully then our symbols mature as well. A problem arises when we get stuck in the mire of the many selves and we don’t mature, we just grow old.

Buddhists who revere the Buddha in the full sense of the word should have two sorts of symbols with them, to serve as reminders of their tradition —

The first is called Buddha-nimitta. These are representatives of the Buddha, such as Buddha images or stupas in which relics of the Buddha are placed.

In Mahayana, such as the Pure Land practice and Vajrayana, the symbols of the Buddha-nimitta are the “Cosmic” Buddhas and the Bodhisattvas. In these remembrances we are put in mind of the qualities of enlightenment itself.

The second is Buddha-guna. These are the qualities that form the inner symbol of the Buddha. The inner symbol is the authentic practice of his teachings. Examples of these are the Eightfold Path, the Perfections, whether the Ten of the Pali or the Six of the Mahayana or the Ten of later Mahayana. One practices in this way is safe from enemies such as temptation and mortality. In Pure Land Buddhism this might manifest as the recitation of the name. In Vajrayana this might be the use of a mantra throughout the day to help focus the mind or special vows and commitments to help purify the mind.

In these practices the mental committee is pacified, calmed and gently integrated into a holistic “being” or presence. There is no longer a need to put words in the Buddha’s mouth, create new religious views, or generate new strategies. As we practice and the mind is pacified we also mature. The committee in the mind makes peace with itself. We’re not just growing old, we are growing up.

You can visit us by clicking here.