The Bodhisattva Vow In Theory

|

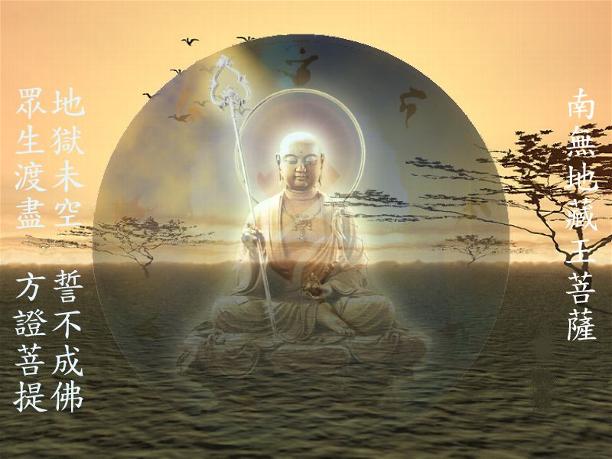

| Ksitigarba |

In theory the Bodhisattva Vow looks very cool and altruistic. I've presented here an argument justifying the teaching. The Bodhisattva Ideal has some very real problems when filtered through the teachings of the Buddha, but in order to be fair and have the appearance of unbiasedness I present this article to you.

This is a rationale for the popular Mahayana theory is that a Bodhisattva is a higher ideal of spiritual aspiration than that of the Arahant. It is usually taught in Mahayana that the goal of the Arahant is only nirvana. This is the extinction of the asravas on the individual level; whereas the goal of the Bodhisattva is bodhi, enlightenment, or sometimes referred to as “spiritual awakening”, of sometimes oneself, but usually postponing that goal until others have reached it. The asravas are the four currents of ignorance, desire for sensory gratification, craving for self-existence, and attachment to views or opinions. The removal of these is the path to the enlightenment of the whole world, Buddhahood. The usual explanation misrepresents both the situation and wisdom of the Arahant. An arahant is by definition a fully enlightened being. A bodhisattva, by definition, is a being on the way to enlightenment. The focus is different. While the Arahant has a laser-like focus on practice and goal, the Bodhisattva uses a broader brush.

Like the Arahant, the Bodhisattva ought to understand that the extinction of the asravas is not an end itself, but it is part of a greater reality that surpasses one’s own individual freedom. This is made clear in both the Pali and Mahayana commentaries alike. No one exists in a vacuum; everyone is part of a spiritual reality that is much greater than one’s self. There are both one’s own practice and that practice’s influence of others. The two are undividable because the self, neither my self nor any other self, is not real in and of itself. The Four Noble Truths are the catalyst for the seemingly impossible four-part vow that determines the Bodhisattva’s life.

Sentient Beings are numberless; I vow to save them.

Desires are inexhaustible; I vow to end them.

Dharma gates are boundless; I vow to enter them.

Buddha's way is unsurpassable; I vow to become it.

The path of the Bodhisattva starts at Bodhicitta. The most famous definition of bodhicitta appears in Maitreya's Abhisamayalankara:

Longing to attain complete enlightenment.

This has twin aspects or purposes:

1. Focusing on sentient beings with compassion, and

It is said that the Bodhisattvas defer their own experience of nirvana, escape from the threefold realm of mortal existence in life and death wandering in Samsara so that they can help others along the path to enlightenment. The tradition goes, twin virtues of wisdom and compassion distinguish the Bodhisattvas from those of the Two Vehicles of Hinayana, aka Theravada, as if Theravada does not advocate wisdom and compassion. Persons who do not understand the nature of the aggregates, enlightenment or the Path, say this.

Why do they say this? Let’s look at the vow again to see if we can find an answer. What does this actually swear to do? If we understood the concept of hongaku and Buddha-nature the answer would seem obvious.

Sentient Beings are numberless; I vow to save them.

Sentient beings are indeed numberless so how can one seriously aspire to save them all? To say the completion of this vow is impossible evades the Buddha’s teachings. The vast majority of people are materialists. Even the dominant religion in the West, Christianity, is essentially a materialistic viewpoint and it has infected its descendant faiths.

Materialists maintain that the physical or material world that can be measured and touched is the only "reality." Some spiritual traditions see the physical as mere illusion--or something inherently corrupt that exists in order to be transcended, and the spiritual as the ultimate truth. These are two extremes. Both contain a kernel of truth and that is one reason why they are so attractive and almost believable.

Buddhism regards life as the unity of the physical and the spiritual. It views all things, whether material or spiritual, seen or unseen, as manifestations of the same ultimate universal law or source of life, the original emptiness often called dharmadhatu. The physical and spiritual aspects of our lives are completely inseparable and equally significant. In Japanese this is expressed as shikishin funi. Shiki refers to all matter and physical phenomena, including the human body. Shin refers to all spiritual, unseen phenomena, including reason, faith, emotion and volition. Funi literally means "two but not two."

Sentient beings are infinite throughout the universe, throughout time, throughout all planes of existence. It is impossible for me to save them all, but that is the vow. How can we hope to do this? We do this by remembering that all beings are essentially one. Each being is unique, a unique manifestation of life and experience and yet we are all participants in the one and the same life, composed of the same matter and sharing the same life. To enlighten one self is to enlighten all. This is the law of the conservation of energy: nothing is created or destroyed. It merely transforms. This is true on the material level.

On the “spiritual” level if one person becomes enlightened, then everyone is elevated. It is an evolutionary process. If I save myself with the intention of saving all sentient beings then in a very real sense I have saved all sentient beings in that my vision of them changes. They participate in the salvation because it is my vision of them that furthers their enlightenment. As my view of the world changes so does my interpretation of the events that take place in that world. Every moment of life is an event; every person is an event that is happening in the present moment.

When the average person looks out he sees only average people. It is said that when the Arahant looks out he sees only arahants. When a bodhisattva sees he sees only bodhisattvas. I’m not sure how true this saying is; it depends on how one views and defines an arahant and bodhisattva. When the ego is conquered how could the Arahant see anyone? By definition and arahant is an enlightened being. This is the secret of the Bodhisattva Vow because it is also said, “to a Buddha all beings appear as Buddhas.” This is because a Buddha sees things, even people, as they really are. When we see things as they are then all sentient beings become enlightened.

Do we really want to end our desires? Very few people really want to end their desires. Cigarette smokers and alcoholics speak volumes about ending their addictions to their drugs of choice but few actually let go of them. Some people have the desire to eat tasty food or organic foods; some have the desire to be around their loved ones; and others might have the desire for a comfortable home. Are these desires wrong in the Buddhist sense? No, they are not, but these aren’t the desires that the Buddha was talking about.

When the Buddha talked about what we call “desire” he used the word tanha and generally translated as “craving.” It means thirst. In Sanskrit you might recognize it more readily, đhiršt (pronounced tthirsht similar to the German word that became the English “thirst”). Using this word shows that desire is not unusual, in fact it is normal to thirst.

When we take our cravings to the point of addiction then we have a problem. I used to like Kit Kat bars, I still do to be honest, but I had taken the desire for Kit Kat Bars to the point of not being able to make it through the day without a half dozen of them. It is when we allow our thirst to become obsession that we run into problems. It is this desire that we are to control and eliminate. Anything can become an obsession. Millions seem to be obsessed with Face Book, others with reality shows, and still others with videos, these obsessions are no more productive than the addiction to drugs and just as harmful. When we see things as they are then the obsessions disappear.

Dharma gates are boundless; I vow to enter them.

Dharma gates really are boundless. We speak of 84,000 dharma gates. This refers to the 84,000 verses in the Pali Canon. Over time the number 84,000 became synonymous with infinity. There is only one real dharma gate that needs to be entered: seeing things as they are. The rest of it is getting to that point.

It is easy to see the truth of emptiness. It is not a terribly hard intellectual property. It is the direct experience of emptiness that requires a lot of work.

So what is emptiness? In original Buddhism anatta, “no self”, is the key concept. Simply put the teaching is that we have no essence that we can call an autonomous self-existence. At any given moment we are simply an event composed of forms within forms, perceptions within perceptions, conceptions within conceptions, volitions within volitions and consciousness within consciousnesses propelled by karma.

In Mahayana shunyata, “emptiness”, is the key concept. Emptiness says that all other selves are like our own self, lacking in autonomous self-existence. Many non-Buddhists take this to mean “nihilism” but this is a misconception. Things do exist, just not the way we thinks they do. When we have a direct experience of emptiness then we actually see the way things are. We have entered all the Dharma gates.

Buddha's way is unsurpassable; I vow to become it.

The fourth part of the vow sometimes reads “The Buddha’s way is unattainable, I vow to attain it.” This, however, contradicts the Heart Sutra that maintains there “is no attainment and nothing to attain”. The Heart Sutra is possibly the most important scripture in the Zen sect so the vow must reflect the intention of the Sutra. The fourth part of the vow has an interesting wording in the Zen version used here. The Buddha’s way is unsurpassable because it is the ultimate in human possibility. There is nothing beyond it as it represents the total union with all there is becoming one with it.

Yoichi Kawada, in his brilliant paper entitled Humanity, Earth and the Universe, says, “Shakyamuni discerned the most fundamental life of the universe and his oneness with it in the depths of his own life.

“According to the Udåna, Shakyamuni names this fundamental life, Dhamma.4 His enlightenment reveals that inside his life, in his “inner cosmos,” there exists a vast universal life—Dhamma, which is the brilliant sun-like force that eradicates all earthly desires and fundamental darkness. This inner cosmos and the greater universe are the one and the same.”

The Bodhisattva Vow has a unique place in Buddhism. It is recited after Refuge in almost every Mahayana ceremony. In Zen it is one of the vows taken by a monk and layperson alike during the Full Moon ceremony. In Pure Land Buddhism it has another implication. It has to do with trust in the Buddhas, what we might call “faith”. It is the trust in one’s own true nature and this means having the same trust on the compassion and wisdom of all the Buddhas, especially Amitabha Buddha. There is implicit in this faith a conviction that the Bodhisattva Vow has been made by all the Buddhas and has already been fulfilled.